Urdu

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Urdu (Urdu: اردو, IPA: [ˈʊrduː] (![]() listen)) is the national language and one of the two official languages of Pakistan (the other being English), and one of 22 scheduled languages of India, as an official language of five Indian states. Based on the Hindi dialect of Delhi, its vocabulary developed under Persian and Turkic influence over the course of almost 900 years.[4] Urdu was mainly developed in Uttar Pradesh in the Indian Subcontinent, but began taking shape during the Delhi Sultanate as well as Mughal Empire (1526–1858) in South Asia. It is the means of communication between the people from various provinces and regions of Pakistan. Due to historical affinities and a large number of Afghan refugees in Pakistan, Urdu is already read, understood and spoken by most Afghans.[5]

listen)) is the national language and one of the two official languages of Pakistan (the other being English), and one of 22 scheduled languages of India, as an official language of five Indian states. Based on the Hindi dialect of Delhi, its vocabulary developed under Persian and Turkic influence over the course of almost 900 years.[4] Urdu was mainly developed in Uttar Pradesh in the Indian Subcontinent, but began taking shape during the Delhi Sultanate as well as Mughal Empire (1526–1858) in South Asia. It is the means of communication between the people from various provinces and regions of Pakistan. Due to historical affinities and a large number of Afghan refugees in Pakistan, Urdu is already read, understood and spoken by most Afghans.[5]

Urdu is a standardized register of Hindustani, and is thus mutually intelligible with Standard Hindi. The grammatical description in this article concerns this standard Urdu. The original language of the Mughals was Chagatai, a Turkic language, but after their arrival in South Asia, they came to adopt Persian. Gradually, the need to communicate with local inhabitants led to a composition of Sanskrit-derived languages, written in the Perso-Arabic script and with literary conventions and specialised vocabulary being retained from Persian, Arabic and Turkic; the new standard was eventually given its own name of Urdu.[6]

Urdu is often contrasted with Hindi, another standardised form of Hindustani. The main differences between the two are that Standard Urdu is conventionally written in Nastaliq calligraphy style of the Perso-Arabic script and draws vocabulary from Persian, Arabic,Turkish and local languages[7] while Standard Hindi is conventionally written in Devanāgarī and draws vocabulary from Sanskrit comparatively[8] more heavily. Most linguists nonetheless consider Urdu and Hindi to be two standardized forms of the same language;[9][10] others classify them separately [11], while some consider any differences to be sociolinguistic.[12] Mutual intelligibility decreases in literary and specialized contexts. Furthermore, due to religious nationalism since the partition of British India and consequent continued communal tensions, native speakers of both Hindi and Urdu increasingly assert them to be completely distinct languages.

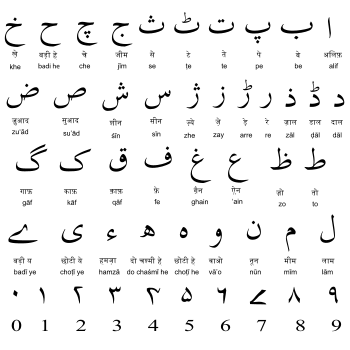

Urdu is generally written from right to left just like Arabic and Persian. Urdu has 39 basic letters and 13 extra characters, all together 52 and most of these letters are from Arabic and a small quantity from Persian. It has almost all the 'sounds' available in any other language spoken in the world.[4]

Contents |

History

There are different theories that have been proposed about the emergence of the Urdu language, but they all stand close and similar. The most prominent and established theory suggests that Urdu developed after the Muslim invasion of the Indian subcontinent by Persian and Turkic dynasties from the 11th century onwards.[13] For the first time Sultan Mahmud, the greatest ruler of the Ghaznavid empire, conquered Punjab in early 11th century. Later on, the Ghurids invaded the northern Indian subcontinent in the 12th century who were then followed by the Delhi Sultanate. Muslim armies comprised of soldiers of different origins and ethnicities who spoke different languages. Interaction among these soldiers and with the locals led to the development of a new language, mutually comprehensible by all. Urdu, therefore, developed as a hybrid version of Hindustani language which borrowed extensively its vocabulary from Arabic, Persian, and Turkic languages.

Later on, during the Mughal Empire, the development of Urdu was further strengthened and started to emerge as a new language.[14] The official language of the Ghurids, Delhi Sultanate, the Mughal Empire, and their successor states, as well as the cultured language of poetry and literature, was Persian, while the language of religion was Arabic. Most of the Sultans and nobility in the Sultanate period were Turks from Central Asia who spoke Turkic as their mother tongue. The Mughals were also from Central Asia, they spoke Chagatai Turkic as their first language; however the Mughals later adopted Persian. Persian became the preferred language of the Muslim elite of north India before the Mughals entered the scene. Babur's mother tongue was a Turkic language and he wrote exclusively in Turkic. His son and successor Humayun also spoke and wrote in this Turkic language. Muzaffar Alam, a noted scholar of Mughal and Indo-Persian history, asserts that Persian became the lingua franca of the empire under Akbar for various political and social factors due to its non-sectarian and fluid nature.[15]

Urdu's vocabulary remains heavily influenced by the Persian language.[16] Since the 19th century, English started to replace Persian as the official language in India and it also contributed to influence the Urdu language. As of today, Urdu's vocabulary is strongly influenced by the English language.

Speakers and geographic distribution

There are between 60 and 70 million self-identified native speakers of Urdu: There were 52 million in India per the 2001 census, some 6% of the population;[17] 12 million in Pakistan in 2008, or 14%;[18] and several hundred thousand apiece is the United Kingdom, Saudi Arabia, United States, and Bangladesh, where it is called "Bihari".[1] However, a knowledge of Urdu allows one to speak with far more people than that, as Hindi-Urdu is the fourth most commonly spoken language in the world, after Mandarin, English, and Spanish.[2][19]

Due to interaction with other languages, Urdu has become localized wherever it is spoken, including in Pakistan itself. Urdu in Pakistan has undergone changes and has lately incorporated and borrowed many words from Pakistani languages like Pashto, Punjabi and Sindhi, thus allowing speakers of the language in Pakistan to distinguish themselves more easily and giving the language a decidedly Pakistani Flavour. Similarly, the Urdu spoken in India can also be distinguished into many dialects like Dakhni (Deccan) of South India, and Khariboli of the Punjab region since recent times. Because of Urdu's similarity to Hindi, speakers of the two languages can usually understand one another at a basic level if both sides refrain from using specialized vocabulary. Some linguists count them as being part of the same diasystem.[20][21] and contend that they are considered as two different languages for socio-political reasons.[22] In Pakistan Urdu is mostly learned as a second or a third language as nearly 93% of Pakistan's population has a mother tongue other than Urdu. Despite this, Urdu was chosen as a token of unity and as a lingua franca so as not to give any native Pakistani language preference over the other. Urdu is therefore spoken and understood by the vast majority in some form or another, including a majority of urban dwellers in such cities as Karachi, Lahore, Rawalpindi, Islamabad, Multan, Faisalabad, Hyderabad, Peshawar, Quetta, Jhang and Sargodha. It is written, spoken and used in all Provinces/Territories of Pakistan despite the fact that the people from differing provinces may have different indigenous languages, as from the fact that it is the "base language" of the country. For this reason, it is also taught as a compulsory subject up to higher secondary school in both English and Urdu medium school systems. This has produced millions of Urdu speakers from people whose mother tongue is one of the State languages of Pakistan such as Punjabi, Pashto, Sindhi, Balochi, Potwari, Hindko, Pahari, Saraiki, and Brahui but they can read and write only Urdu. It is absorbing many words from the regional languages of Pakistan. This variation of Urdu is sometimes referred to as Pakistani Urdu. So while most of the population is conversant in Urdu, it is the mother tongue only of an estimated 7% of the population, mainly Muslim immigrants (known as Muhajir in Pakistan) from different parts of South Asia (India, Burma, Bangladesh etc.). The regional languages are also being influenced by Urdu vocabulary. There are millions of Pakistanis whose mother tongue is not Urdu, but since they have studied in Urdu medium schools, they can read and write Urdu along with their native language. Most of the nearly five million Afghan refugees of different ethnic origins (such as Pashtun, Tajik, Uzbek, Hazarvi, and Turkmen) who stayed in Pakistan for over twenty-five years have also become fluent in Urdu. With such a large number of people(s) speaking Urdu, the language has in recent years acquired a peculiar Pakistani flavour further distinguishing it from the Urdu spoken by native speakers and diversifying the language even further.

A great number of newspapers are published in Urdu in Pakistan, including the Daily Jang, Nawa-i-Waqt, Millat, among many others (see List of newspapers in Pakistan#Urdu-language newspapers).

In India, Urdu is spoken in places where there are large Muslim minorities or cities which were bases for Muslim Empires in the past. These include parts of Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Bihar, Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra (Marathwada), Karnataka and cities namely Lucknow, Delhi, Meerut, Saharanpur, Muzaffarnagar, Roorkee, Deoband, Moradabad, Bijnor, Najibabad, Rampur, Aligarh, Allahabad, Gorakhpur, Agra, Kanpur, Badaun, Bhopal, Hyderabad, Aurangabad, Bengaluru, Kolkata, Mysore, Patna, Gulbarga, Nanded, Bidar, Ajmer, and Ahmedabad.[23] Some Indian schools teach Urdu as a first language and have their own syllabus and exams. Indian madrasahs also teach Arabic as well as Urdu. India has more than 3,000 Urdu publications including 405 daily Urdu newspapers. Newspapers such as Sahara Urdu, Daily Salar, Hindustan Express, Daily Pasban, Siasat Daily, The Munsif Daily and Inqilab are published and distributed in Bengaluru, Mysore, Hyderabad, and Mumbai (see List of newspapers in India).

Outside South Asia, it is spoken by large numbers of migrant South Asian workers in the major urban centres of the Persian Gulf countries and Saudi Arabia. Urdu is also spoken by large numbers of immigrants and their children in the major urban centres of the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Germany, Norway, and Australia. Along with Arabic, Urdu is among the immigrant languages with most speakers in Catalonia.[24]

Official status

Urdu is the national and one of the two official languages (Qaumi Zabaan) of Pakistan, the other being English, and is spoken and understood throughout the country, while the state-by-state languages (languages spoken throughout various regions) are the provincial languages. It is used in education, literature, office and court business.[25] It holds in itself a repository of the cultural and social heritage of the country.[26] Although English is used in most elite circles, and Punjabi has a plurality of native speakers, Urdu is the lingua franca and national language in Pakistan.

Urdu is also one of the officially recognised languages in India and has official language status in the Indian states of Uttar Pradesh, Bihar,[27], Andhra Pradesh, Jarkhand, Jammu and Kashmir and the national capital, New Delhi.

In Jammu and Kashmir, section 145 of the Kashmir Constitution provides: "The official language of the State shall be Urdu but the English language shall unless the Legislature by law otherwise provides, continue to be used for all the official purposes of the State for which it was being used immediately before the commencement of the Constitution." As of 2010, the English language continues to be used as an official language for more than 90% of official work in Kashmir.[28] There are ongoing efforts to make Kashmiri and Dogri, spoken as mother tongues by nearly 80% of the population of Indian-administered Kashmir, as official languages alongside English.

The importance of Urdu [29] in the Muslim world is visible in the Holy cities of Mecca and Medina in Saudi Arabia, where most informational signage is written in Arabic, English and Urdu, and sometimes in other languages.

Dialects

Urdu has four recognised dialects: Dakhni, Rekhta, and Modern Vernacular Urdu (based on the Khariboli dialect of the Delhi region). Dakhni (also known as Dakani, Deccani, Desia, Mirgan) is spoken in Deccan region of southern India. It is distinct by its mixture of vocabulary from Marathi and Telugu language, as well as some vocabulary from Arabic, Persian and Turkish that are not found in the standard dialect of Urdu. In terms of pronunciation, the easiest way to recognize a native speaker is their pronunciation of the letter "qāf" (ﻕ) as "kh" (ﺥ). Dakhini is widely spoken in all parts of Maharashtra, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu. Urdu is read and written as in other parts of India. A number of daily newspapers and several monthly magazines in Urdu are published in these states.

Pakistani variant of the language spoken in Pakistan; it becomes increasingly divergent from the Indian dialects and forms of Urdu as it has absorbed many loan words, proverbs and phonetics from Pakistan's indigenous languages such as Pashto, Panjabi and Sindhi. Furthermore, due to the region's history, the Urdu dialect of Pakistan draws heavily from the Persian and Arabic languages, and the intonation and pronunciation are informal compared with corresponding Indian dialects.

In addition, Rekhta (or Rekhti), the language of Urdu poetry, is sometimes counted as a separate dialect, one famously used by several British Indian poets of high acclaim in the bulk of their work. These included Mirza Ghalib, Mir Taqi Mir and Muhammad Iqbal, the national poet-philosopher of Pakistan.

Phonology

Grammar

Vocabulary

Urdu has a vocabulary rich in words with Indic and Middle Eastern origins. The language's Indic base has been enriched by borrowing from Persian and Arabic. There are also a small number of borrowings from Turkish, Portuguese, and more recently English. Many of the words of Arabic origin have been adopted through Persian and have different nuances of meaning and usage than they do in Arabic. Other words have exactly the same pronunciation, spelling, and meaning. For instance, the words "Sawaal" (lit. "Question") and "Jawaab" (lit. "Answer") are exactly the same in both Urdu and Arabic. An Urdu speaker needs only to visit Iran to discover that many words that are used daily in Urdu have different usages and meanings in Iranian Persian. This may be because the Persian found in Urdu is closer in a number of ways to Dari Persian.

Levels of formality

Urdu in its less formalised register has been referred to as a rekhta (ریختہ, [reːxt̪aː]), meaning "rough mixture". The more formal register of Urdu is sometimes referred to as zabān-e-Urdu-e-mo'alla (زبان اردو معلہ [zəbaːn eː ʊrd̪uː eː moəllaː]), the "Language of the Exalted Camp" referring to the Imperial Bazar.[30]

The etymology of the word used in the Urdu language for the most part decides how polite or refined your speech is. For example, Urdu speakers would distinguish between پانی pānī and آب āb, both meaning "water" for example, or between آدمی ādmi and مرد mard, meaning "man". The former in each set is used colloquially and has older Hindustani origins, while the latter is used formally and poetically, being of Persian origin.

If a word is of Persian or Arabic origin, the level of speech is considered to be more formal and grand. Similarly, if Persian or Arabic grammar constructs, such as the izafat, are used in Urdu, the level of speech is also considered more formal and grand. If a word is inherited from Sanskrit, the level of speech is considered more colloquial and personal.[31]

That distinction has likenesses with the division between words from a French or Old English origin while speaking English.

Politeness

Urdu is supposed to be a subtle and polished language; a host of words are used in it to show respect and politeness. This emphasis on politeness, which is reflected in the vocabulary, is known as adab and to some extent as takalluf in Urdu. These words are generally used when addressing elders, or people with whom one is not acquainted. For example, the English pronoun 'you' can be translated into three words in Urdu the singular forms tu (derogatory or highly informal) and tum (informal and showing intimacy called "apna pan" in Urdu) and the plural form āp (formal and respectful).

Another example is the English affirmation 'yes', which can be translated into two words in Urdu according to the level of politeness one wishes to maintain, and there are subtle unspoken laws that govern the use of these two words together, a remnant of the royal history of the language. The word "haan" is often used colloquially and informally, and the word "ji" is used in more formal conversation or when addressing an elder. The combination "ji haan" is the politest way to say 'yes', while the combination "haan ji" is highly likely to be considered impolite, though certainly not offensive.

Writing system

Persian script

Urdu is written right-to left in an extension of the Persian alphabet, which is itself an extension of the Arabic alphabet. Urdu is associated with the Nastaʿlīq script style of Persian calligraphy, whereas Arabic is generally written in the modernized Naskh style. Nasta’liq is notoriously difficult to typeset, so Urdu newspapers were hand-written by masters of calligraphy, known as katib or khush-navees, until the late 1980s.

Kaithi script

Urdu was also written in the Kaithi script. A highly-Persianized and technical form of Urdu was the lingua franca of the law courts of the British administration in Bengal, Bihar, and the North-West Provinces & Oudh. Until the late 19th century, all proceedings and court transactions in this register of Urdu were written officially in the Persian script. In 1880, Sir Ashley Eden, the Lieutenant-Governor of Bengal abolished the use of the Persian alphabet in the law courts of Bengal and Bihar and ordered the exclusive use of Kaithi, a popular script used for both Urdu and Hindi.[32] Kaithi's association with Urdu and Hindi was ultimately eliminated by the political contest between these languages and their scripts, in which the Persian script was definitively linked to Urdu.

Devanagari script

More recently in India, Urdu speakers have adopted Devanagari for publishing Urdu periodicals and have innovated new strategies to mark Urdū in Devanagari as distinct from Hindi in Devanagari.[33] The popular Urdu monthly magazine, महकता आंचल (Mahakta Anchal), is published in Delhi in Devanagari in order to target the generation of Muslim boys and girls who do not know the Persian script.[34] Such publishers have introduced new orthographic features into Devanagari for the purpose of representing Urdu sounds. One example is the use of अ (Devanagari a) with vowel signs to mimic contexts of ع (‘ain). To Urdu publishers, the use of Devanagari gives them a greater audience, but helps them to preserve the distinct identity of Urdu when written in Devanagari.

Roman script

Urdu is occasionally also written in the Roman script. Roman Urdu has been used since the days of the British Raj, partly as a result of the availability and low cost of Roman movable type for printing presses. The use of Roman Urdu was common in contexts such as product labels. Today it is regaining popularity among users of text-messaging and Internet services and is developing its own style and conventions. Habib R. Sulemani says, "The younger generation of Urdu-speaking people around the world, especially Pakistan, are using Romanised Urdu on the Internet and it has become essential for them, because they use the Internet and English is its language. Typically, in that sense, a person from Islamabad in Pakistan may chat with another in Delhi in India on the Internet only in Roman Urdū. They both speak the same language but would have different scripts. Moreover, the younger generation of those who are from the English medium schools or settled in the west, can speak Urdu but can’t write it in the traditional Arabic script and thus Roman Urdu is a blessing for such a population."[35] Roman Urdu also holds significance among the Christians of Pakistan and North India. Urdū was the dominant native language among Christians of Karachi and Lahore in present-day Pakistan and Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh Rajasthan in India, during the early part of the nineteenth and twentieth century, and is still used by Christians in these places. Pakistani and Indian Christians often used the Roman script for writing Urdū. Thus Roman Urdū was a common way of writing among Pakistani and Indian Christians in these areas up to the 1960s. The Bible Society of India publishes Roman Urdū Bibles which enjoyed sale late into the 1960s (though they are still published today). Church songbooks are also common in Roman Urdū. However, the usage of Roman Urdū is declining with the wider use of Hindi and English in these states.

Transliteration of Urdu

Usually, bare transliterations of Urdu into Roman letters omit many phonemic elements that have no equivalent in English or other languages commonly written in the Latin alphabet. A comprehensive system has emerged with specific notations to signify non-English sounds, but it can only be properly read by someone already familiar with Urdu, Persian, or Arabic for letters such as:ژ خ غ ط ص or ق and Hindi for letters such as ڑ. This script may be found on the Internet, and it allows people who understand the language but without knowledge of their written forms to communicate with each other.

- Examples

| English | Urdu | Transliteration | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hi | السلام علیکم | assalāmu ‘alaikum | lit. "Peace be upon you." (from Arabic) |

| Hello | و علیکم السلام | waˈalaikum assalām | lit. "And upon you, peace." Response to assalāmu ‘alaikum (from Arabic) |

| Hello | (آداب (عرض ہے | ādāb (arz hai) | lit. "Regards (are expressed)", a very formal secular greeting |

| Goodbye | خُدا حافظ | khuda hāfiz | lit. "May God be your Guardian" (from Persian). |

| yes | ہاں | hān | casual |

| yes | جی | jī | formal |

| yes | جی ہاں | jī hān | confident formal |

| no | نہ | nā | casual |

| no | نہیں، جی نہیں | nahīn, jī nahīn | casual; jī nahīn formal |

| please | مہربانی | meharbānī | lit. "kindness" Also used for "thank you" |

| thank you | شُکریہ | shukrīā | from Arabic shukran |

| Please come in | تشریف لائیے | tashrīf laīe | lit. "(Please) bring your honour" |

| Please have a seat | تشریف رکھیئے | tashrīf rakhīe | lit. "(Please) place your honour" |

| I am happy to meet you | آپ سے مل کر خوشی ہوئی | āp se mil kar khushī hūyī | |

| Do you speak English? | کیا آپ انگریزی بولتے ہیں؟ | kya āp angrezī bolte hain? | lit. "Do you speak English?" |

| I do not speak Urdu. | میں اردو نہیں بولتا/بولتی | main urdū nahīn boltā/boltī | boltā is masculine, boltī is feminine |

| My name is ... | میرا نام ۔۔۔ ہے | merā nām .... hai | |

| Which way to Lahore? | لاھور کس طرف ہے؟ | lāhaur kis taraf hai? | lit. "What direction is Lahore in?" |

| Where is Lucknow? | لکھنؤ کہاں ہے؟ | Lakhnau kahān hai | |

| Urdu is a good language. | اردو اچھی زبان ہے | urdū achhī zabān hai | lit. "Urdu is a good language" |

Sample text

The following is a sample text in zabān-e urdū-e muʻallā (formal Urdu), of the Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (by the United Nations):

Nastaliq text (used in Pakistan and India)

- دفعہ 1: تمام انسان آزاد اور حقوق و عزت کے اعتبار سے برابر پیدا ہوۓ ہیں۔ انہیں ضمیر اور عقل ودیعت ہوئی ہے۔ اس لئے انہیں ایک دوسرے کے ساتھ بھائی چارے کا سلوک کرنا چاہئے

Transliteration (ALA-LC)

- Dafʻah 1: Tamām insān āzād aur ḥuqūq o ʻizzat ke iʻtibār se barābar paidā hu’e haiṇ. Unheṇ zamīr aur ʻaql wadīʻat hu’ī he. Isli’e unheṇ ek dūsre ke sāth bhā’ī chāre kā sulūk karnā chāhi’e.

IPA Transcription

- d̪əfa ek: t̪əmam ɪnsan azad̪ ɔɾ hʊquq o ʔizət̪ ke ɪʔt̪ɪbaɾ se bəɾabəɾ pɛda hʊe hẽ. ʊnʱẽ zəmiɾ ɔɾ ʔəqəl ʋədiət̪ hʊi he. ɪslɪe ʊnʱẽ ek d̪usɾe ke sat̪ʰ bʱai tʃaɾe ka sʊluk kəɾna tʃahɪe.

Gloss (word-for-word)

- Article 1: All humans free[,] and rights and dignity *('s) consideration from equal born are. To them conscience and intellect endowed is. Therefore, they one another *('s) with brotherhood *('s) treatment do must.

Translation (grammatical)

- Article 1: All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience. Therefore, they should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

Note: *('s) represents a possessive case which when written is preceded by the possessor and followed by the possessed, unlike the English 'of'.

Literature

Urdu has become a literary language only in recent centuries, as Persian and Arabic were formerly the idioms of choice for "elevated" subjects. However, despite its relatively late development, Urdu literature boasts some world-recognised artists and a considerable corpus.

Prose

Religious

Urdu holds the largest collection of works on Islamic literature and Sharia after Arabic. These include translations and interpretation of Qur'an, commentary on Hadith, Fiqh, history, spirituality, Sufism and metaphysics. A great number of classical texts from Arabic and Persian, have also been translated into Urdu. Relatively inexpensive publishing, combined with the use of Urdu as a lingua franca among Muslims of South Asia, has meant that Islam-related works in Urdu far outnumber such works in any other South Asian language. Popular Islamic books, originally written in Urdu.

Astrology It is an interesting fact to note that a treatise on Astrology had been penned down in Urdu by Pandit Roop Chand Joshi in the eighteenth century. The book is known as LAL KITAB. It is widely popular in the North India among the Astrologers and it was written at a time when Urdu was also very much spoken in the Brahmin families of North India.

Literary

Secular prose includes all categories of widely known fiction and non-fiction work, separable into genres.{

The dāstān, or tale, a traditional story which may have many characters and complex plotting. This has now fallen into disuse.

The afsāna, or short story, probably the best-known genre of Urdu fiction. The best-known afsāna writers, or afsāna nigār, in Urdu are Munshi Premchand, Saadat Hasan Manto, Rajinder Singh Bedi, Krishan Chander, Qurratulain Hyder (Qurat-ul-Ain Haider), Ismat Chughtai, Ghulam Abbas, and Ahmad Nadeem Qasimi. Towards the end of last century Paigham Afaqui's novel Makaan appeared with a reviving force for Urdu novel resulting into writing of novels getting a boost in Urdu literature and a number of writers like Ghazanfer, Abdus Samad, Sarwat Khan and Musharraf Alam Zauqi have taken the move forward. Munshi Premchand, became known as a pioneer in the afsāna, though some contend that his were not technically the first as Sir Ross Masood had already written many short stories in Urdu.

Novels form a genre of their own, in the tradition of the English novel.

Other genres include saférnāma (travel story), mazmoon (essay), sarguzisht(account/narrative), inshaeya(satirical essay), murasela(editorial), and khud navvisht (autobiography).

Poetry

Urdu has been one of the premier languages of poetry in South Asia for two centuries, and has developed a rich tradition in a variety of poetic genres. The 'Ghazal' in Urdu represents the most popular form of subjective music and poetry, while the 'Nazm' exemplifies the objective kind, often reserved for narrative, descriptive, didactic or satirical purposes. Under the broad head of the Nazm we may also include the classical forms of poems known by specific names such as 'Masnavi' (a long narrative poem in rhyming couplets on any theme: romantic, religious, or didactic), 'Marsia' (an elegy traditionally meant to commemorate the martyrdom of Hazrat Husayn ibn Ali, grandson of Muhammad, and his comrades of the Karbala fame), or 'Qasida' (a panegyric written in praise of a king or a nobleman), for all these poems have a single presiding subject, logically developed and concluded. However, these poetic species have an old world aura about their subject and style, and are different from the modern Nazm, supposed to have come into vogue in the later part of the nineteenth century.

Probably the most widely recited, and memorised genre of contemporary Urdu poetry is nāt—panegyric poetry written in praise of the Prophet Muhammad. Nāt can be of any formal category, but is most commonly in the ghazal form. The language used in Urdu nāt ranges from the intensely colloquial to a highly Persified formal language. The great early 20th century scholar Imam Ahmed Rida Khan, who wrote many of the most well known nāts in Urdu (the collection of his poetic work is Hadaiq-e-Baqhshish), epitomised this range in a ghazal of nine stanzas (bayt) in which every stanza contains half a line each of Arabic, Persian, formal Urdu, and colloquial Hindi. The same poet composed a salām—a poem of greeting to the Prophet Muhammad, derived from the unorthodox practice of qiyam, or standing, during the mawlid, or celebration of the birth of the Prophet—Mustafā Jān-e Rahmat, which, due to being recited on Fridays in some Urdu speaking mosques throughout the world, is probably the more frequently recited Urdu poems of the modern era. Another notable nāt writer (natkhwan) is Maulana Shabnam Kamali whose nāts have been widely appreciated & acknowledged.

Another important genre of Urdu prose are the poems commemorating the martyrdom of Husayn ibn Ali Allah hiss salam and Battle of Karbala, called noha (نوحہ) and marsia. Anees and Dabeer are famous in this regard.

Terminology

Ash'ār (اشعار) (Couplet). It consists of two lines, Misra (مصرعہ); first line is called Misra-e-oola (مصرع اولی) and the second is called 'Misra-e-sānī' (مصرعہ ثانی). Each verse embodies a single thought or subject (sing) She'r (شعر).

Urdu poetry example

This is Ghalib's famous couplet in which he compares himself to his great predecessor, the master poet Mir:[36]

|

ریختے کے تمہی استاد نہیں ہو غالب

|

||

|

کہتے ہیں اگلے زمانے میں کوئی میر بھی تھا

|

Transliteration

- Rekhta ke tumhinustād tu nahīn ho Ghālib

- Kahte hain agle zamāne men ko'ī Mīr bhī thā

Translation

- You are not the only master of Rekhta*, Ghalib

- They say that in the past there also was someone named Mir.

- Rekhta was the name for the Urdu/Hindi language in Ghalib's days, when the distinction had not yet been made.

Urdu and Hindi

Because of their identical grammar and nearly identical core vocabularies, most linguists do not distinguish between Urdu and Hindi as separate languages — at least not in reference to the informal spoken registers. For them, ordinary informal Urdu and Hindi can be seen as variants of the same language (Hindustani) with the difference being that Urdu is supplemented with a Perso-Arabic vocabulary and Hindi a Sanskritic vocabulary. Additionally, there is the convention of Urdu being written in Persio-Arabic script, and Hindi in Devanagari. The standard, "proper" grammars of both languages are based on Khariboli grammar — the dialect of the Delhi region. So, with respect to grammar, the languages are mutually intelligible when spoken, and can be thought of as two written variants of the same language.

Hindustani is the name often given to this language as it developed over hundreds of years throughout India (which formerly included what is now Pakistan). In the same way that the core vocabulary of English evolved from Old English (Anglo-Saxon) but includes a large number of words borrowed from French and other languages (whose pronunciations often changed naturally so as to become easier for speakers of English to pronounce), what may be called Hindustani can be said to have evolved from Sanskrit while borrowing many Persian and Arabic words over the years, and changing the pronunciations (and often even the meanings) of those words. This usually made the words easier for Hindustani speakers to pronounce and also more pleasant than the coarse original sounds. Therefore, Hindustani is the language as it evolved organically just like many other languages in the world.

Linguistically speaking, Standard Hindi is a form of colloquial Hindustani, with lesser use of Persian and Arabic loanwords, while inheriting its formal vocabulary from Sanskrit; Standard Urdu is also a form of Hindustani, de-Sanskritised, with a significant part of its formal vocabulary consisting of loanwords from Persian and Arabic. The difference, thus is in the vocabulary, and not the structure of the language.

The difference is also sociolinguistic: When people speak Hindustani (i.e., when they are speaking colloquially) speakers who are Muslims will usually say that they are speaking Urdu, and those who are Hindus will typically say that they are speaking Hindi, even though they are speaking essentially the same language.

The two standardised registers of Hindustani — Urdu and Hindi — have become so entrenched as separate languages that often nationalists, both Muslim and Hindu, claim that Urdu and Hindi have always been separate languages. There have been some observations that the "fully standardized" Hindi register is artificial enough to make it partially incomprehensible to many people classified as Hindi speakers.[37][38]

Because of the difficulty in distinguishing between Urdu and Hindi speakers in India and Pakistan and estimating the number of people for whom Urdu is a second language the estimated number of speakers is uncertain and controversial. For further information the reader is referred to the following Wikipedia articles: Hindi-Urdu controversy, Hindustani language and Hindi

Software

The Daily Jang/daily waqt was the first Urdu newspaper to be typeset digitally in Nasta’liq by computer. There are efforts underway to develop more sophisticated and user-friendly Urdu support on computers and the Internet. Nowadays, nearly all Urdu newspapers, magazines, journals, and periodicals are composed on computers via various Urdu software programmes, the most widespread of which is InPage Desktop Publishing package. Microsoft has included Urdu language support in all new versions of Windows and both Windows Vista and Microsoft Office 2007 are available in Urdu through Language Interface Pack[39] support.

Difficulty in learning Urdu

Perso-Arabic script has been extended for Urdu with additional letters ٹ,ڈ,ڑ. In order to Indianise or make the language suitable for the people of South Asia (mainly India and Pakistan), two letters ہ and ی have added dimensions in use. ہ is used independently as any other letter in words such as ہم (we) and باہم(mutual). As an extended use, ہ is also used denote uniquely defined phonetics of South Asian origin. Here it is referred as do-chashmi hey and it follows the nearest letters of the Perso-Arabic script to render the required phonetic. Some example of the words are دھڑکن(heartbeat),بھارت(India). On the other hand ی is used in two vowel forms: Chhoti ye (ی) and Badi ye(ے). Chhoti ye denotes the vowel sound similar to "ea" in the English word beat as in the word (companion) ساتھی. Chhoti ye is also used as the Urdu consonant "Y" as in word یار (companion/friend). Badi ye is supposed to give the sound similar to "a" in the word "late" (full vowel sound - not like a diphthong) as in the word کے (of). However, in the written form both badi ye and chhoti ye are same when the vowel falls in the middle of a word and the letters need to be joint according to the rules of the Urdu grammar . Badi ye is also used to play a supporting role for a diphthong sound such as the English "i" as in the word "bite" as in the word (wine)مے. However, no difference of ye is seen in words such as کیسا(how) where the vowel comes in the middle of the written word. Similarly the letter و is used to denote vowel sound -oo similar to the word "food" as in لوٹ (loot) , "o" similar to the word "vote" as in دو (two) and it is also used as a consonant "w" similar to the word "war" as in وظیفہ (pension). It is also used as a supportive letter in the diphthong construction similar to the "ou" in the word "mount" as in the word کون (who). و is silent in many word of Persian origin such as خواب (dream), خواہش (desire). It has diminutive sound similar to "ou" in words such as "would","could" as in the words خود (self), خوش (happy). The vowel/accent marks (اعراب ) mainly support the core Arabic vowels.Non-Arabic vowels such as -o- in the more (مور- peacock) and the -a- as in Estonia (ایسٹونیا) are referred as مجہول(alien/ ignorant phonetics) and hence are not supported by the vowel/accent marks (اعراب). A description of these vowel marks and the word formation in Urdu can be found at this website.

See also

- Badshah Munir Bukhari

- Ghazal

- Hindi–Urdu controversy

- Hindi-Urdu phonology

- Languages of India

- Languages of Pakistan

- List of Urdu language poets

- List of Urdu language writers

- List of Wikipedias

- National Translation Mission(NTM)

- Persian and Urdu

- Urdu in Aurangabad

- States of India by Urdu speakers

- Uddin and Begum Urdu-Hindustani Romanization

- Urdu Digest

- Urdu Informatics

- Urdu keyboard

- Urdu literature

- Urdu poetry

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Lewis, M. Paul (ed.), 2009. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Sixteenth edition. Dallas, Tex.: SIL International. Online version

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Ethnologue: Statistical Summaries". SIL. 1999. http://www.ethnologue.com/ethno_docs/distribution.asp?by=size. Retrieved 2010-07-19.

- ↑ Linguistic Lineage for Urdu - Ethnologue

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "A brief history of Urdu". BBC. http://www.bbc.co.uk/languages/other/guide/urdu/history.shtml. Retrieved 2010-07-01.

- ↑ "A Historical Perspective of Urdu". National Council for Promotion of Urdu language. http://www.urducouncil.nic.in/pers_pp/index.htm. Retrieved 2007-06-15.

- ↑ Hindi By Yamuna Kachru http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=ooH5VfLTQEQC&pg=PA2&lpg=PA2&dq=urdu+heavy+persian&source=bl&ots=dG3qgmaV95&sig=WivP7AW9eRlTcp4oscBoHCBFEE0&hl=en&ei=9sp8SqzpLI6y-AaM5vxG&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=9#v=onepage&q=urdu%20heavy%20persian&f=false

- ↑ "Bringing Order to Linguistic Diversity: Language Planning in the British Raj". Language in India. http://www.languageinindia.com/oct2001/punjab1.html. Retrieved 2008-05-20.

- ↑ "A Brief Hindi - Urdu FAQ". sikmirza. http://www.oocities.com/sikmirza/arabic/hindustani.html. Retrieved 2008-05-20.

- ↑ "Hindi/Urdu Language Instruction". University of California, Davis. http://mesa.ucdavis.edu/hindiurdu/index.html. Retrieved 2008-05-20.

- ↑ "Ethnologue Report for Hindi". Ethnologue. http://www.ethnologue.org/show_language.asp?code=hin. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- ↑ The Annual of Urdu studies, number 11, 1996, “Some notes on Hindi and Urdu, pp.204

- ↑ "Urdu and it's Contribution to Secular Values". South Asian Voice. http://india_resource.tripod.com/Urdu.html. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ [2]

- ↑ Alam, Muzaffar. "The Pursuit of Persian: Language in Mughal Politics." In Modern Asian Studies, vol. 32, no. 2. (May, 1998), pp. 317–349.

- ↑ [3]

- ↑ "Abstract of speakers’ strength of languages and mother tongues – 2001". Government of India. http://www.censusindia.gov.in/Census_Data_2001/Census_Data_Online/Language/Statement1.htm. Retrieved 2008-05-10.

- ↑ "Ethnologue Report for Pakistan". SIL Ethnologue. http://www.ethnologue.com/show_country.asp?name=pk. Retrieved 2007-10-07.

- ↑ "The World's 10 most influential Languages". Language Today. http://www.andaman.org/BOOK/reprints/weber/rep-weber.htm. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- ↑ "The Range of Hindi and Urdu". Columbia University. http://www.columbia.edu/itc/mealac/pritchett/00urduhindilinks/shacklesnell/104range.pdf. Retrieved 2008-05-20.

- ↑ "About Hindi-Urdu". North Carolina State University. http://sasw.chass.ncsu.edu/fl/faculty/taj/hindi/abturdu.htm. Retrieved 2009–08–09.

- ↑ "Hindi-Urdu Flagship Program". University of Texas at Austin. http://www.hindiurduflagship.org/about/what-is-hindi-urdu.html. Retrieved 2009–08–09.

- ↑ India Travelite: Holy Places - Ajmer

- ↑ [4]

- ↑ In the lower courts in Pakistan, despite the proceedings taking place in Urdu, the documents are in English whilst in the higher courts, ie the High Courts and the Supreme Court, both documents and proceedings are in English.

- ↑ Zia, Khaver (1999), "A Survey of Standardisation in Urdu". 4th Symposium on Multilingual Information Processing, (MLIT-4), Yangon, Myanmar. CICC, Japan

- ↑ "Urdu in Bihar". Language in India. http://www.languageinindia.com/feb2003/urduinbihar.html. Retrieved 2008-05-17.

- ↑ http://jkgad.nic.in/statutory/Rules-Costitution-of-J&K.pdf

- ↑ "Importance Of Urdu". GeoTauAisay.com. http://www.geotauaisay.com/2010/08/the-importance-of-urdu/. Retrieved 2010-08-08.

- ↑ Colin P. Masica, The Indo-Aryan languages. Cambridge Language Surveys (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993). 466.

- ↑ "About Urdu". Afroz Taj (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. http://www.unc.edu/. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- ↑ King, 1994.

- ↑ Ahmad, R., 2006.

- ↑ Delhi Public Library Catalog; Details for: महकता आंचल

- ↑ The News, Karachi, Pakistan: Roman Urdu by Habib R Sulemani

- ↑ Columbia University: Ghazal 36, Verse 11

- ↑ Gerald B. Kelley, Edward C. Dimock, Bhadriraju Krishnamurti (1992). Dimensions of sociolinguistics in South Asia: papers in memory of Gerald B. Kelley. Oxford & IBH Pub. Co.. ISBN 8120405730. http://books.google.com/?id=O8FhAAAAMAAJ. "... policy of Sanskritization resulted in a variety of Hindi which was far removed from everyday usage and became almost incomprehensible to the common man ..."

- ↑ Maria Misra (2007). Vishnu's crowded temple: India since the Great Rebellion. Allan Lane. http://books.google.com/books?id=DvttAAAAMAAJ. "... This linguistic cleansing not only destroyed Hindustani, but in its hyper-purist form rendered Hindi itself incomprehensible to the less well-educated and ...".

- ↑ http://www.microsoft.com/downloads/Browse.aspx?displaylang=ur&productID=38DF6AB1-13D4-409C-966D-CBE61F040027

- Ahmad, Rizwan. 2006. "Voices people write: Examining Urdu in Devanagari". http://www.ling.ohio-state.edu/NWAV/Abstracts/Papr172.pdf

- Alam, Muzaffar. 1998. "The Pursuit of Persian: Language in Mughal Politics." In Modern Asian Studies, vol. 32, no. 2. (May, 1998), pp. 317–349.

- Asher, R. E. (Ed.). 1994. The Encyclopedia of language and linguistics. Oxford: Pergamon Press. ISBN 0-08-035943-4.

- Azad, Muhammad Husain. 2001 [1907]. Aab-e hayat (Lahore: Naval Kishor Gais Printing Works) 1907 [in Urdu]; (Delhi: Oxford University Press) 2001. [In English translation]

- Azim, Anwar. 1975. Urdu a victim of cultural genocide. In Z. Imam (Ed.), Muslims in India (p. 259).

- Bhatia, Tej K. 1996. Colloquial Hindi: The Complete Course for Beginners. London, UK & New York, NY: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-11087-4 (Book), 0415110882 (Cassettes), 0415110890 (Book & Cassette Course)

- Bhatia, Tej K. and Koul Ashok. 2000. "Colloquial Urdu: The Complete Course for Beginners." London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-13540-0 (Book); ISBN 0-415-13541-9 (cassette); ISBN 0-415-13542-7 (book and casseettes course)

- Chatterji, Suniti K. 1960. Indo-Aryan and Hindi (rev. 2nd ed.). Calcutta: Firma K.L. Mukhopadhyay.

- Dua, Hans R. 1992. "Hindi-Urdu as a pluricentric language". In M. G. Clyne (Ed.), Pluricentric languages: Differing norms in different nations. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-012855-1.

- Dua, Hans R. 1994a. Hindustani. In Asher, 1994; pp. 1554.

- Dua, Hans R. 1994b. Urdu. In Asher, 1994; pp. 4863–4864.

- Durrani, Attash, Dr. 2008. Pakistani Urdu.Islamabad: National Language Authority, Pakistan.

- Hassan, Nazir and Omkar N. Koul 1980. Urdu Phonetic Reader. Mysore: Central Institute of Indian Languages.

- Kelkar, A. R. 1968. Studies in Hindi-Urdu: Introduction and word phonology. Poona: Deccan College.

- Khan, M. H. 1969. Urdu. In T. A. Sebeok (Ed.), Current trends in linguistics (Vol. 5). The Hague: Mouton.

- King, Christopher R. 1994. One Language, Two Scripts: The Hindi Movement in Nineteenth Century North India. Bombay: Oxford University Press.

- Koul, Ashok K. 2008. Urdu Script and Vocabulary. Delhi: Indian Institute of Language Studies.

- Koul, Omkar N. 1994. Hindi Phonetic Reader. Delhi: Indian Institute of Language Studies.

- Koul, Omkar N. 2008. Modern Hindi Grammar. Springfield: Dunwoody Press.

- Narang, G. C. and D. A. Becker. 1971. Aspiration and nasalization in the generative phonology of Hindi-Urdu. Language, 47, 646–767.

- Ohala, M. 1972. Topics in Hindi-Urdu phonology. (PhD dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles).

- "A Desertful of Roses", a site about Ghalib's Urdu ghazals by Dr. Frances W. Pritchett, Professor of Modern Indic Languages at Columbia University, New York, NY, USA.

- Phukan, S. 2000. The Rustic Beloved: Ecology of Hindi in a Persianate World, The Annual of Urdu Studies, vol 15, issue 5, pp. 1–30

- The Comparative study of Urdu and Khowar. Badshah Munir Bukhari National Language Authority Pakistan 2003.

- Rai, Amrit. 1984. A house divided: The origin and development of Hindi-Hindustani. Delhi: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-561643-X.

- Snell, Rupert Teach yourself Hindi: A complete guide for beginners. Lincolnwood, IL: NTC

- "The Urdu Language"

- The poisonous potency of script: Hindi and Urdu, ROBERT D. KING

|

||||||||

|

|||||

|

||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||